The First Navy Helicopter Deployment-Operation Crossroads

LCDR Brian Miller, USN (Ret.) NHA Historical Society Executive Committee

In early March of 1946, USS Shangri La (CV 38) got underway from Norfolk, VA bound for San Diego, CA. The ultimate destination was Bikini Atoll and Operation Crossroads. Aboard Shangri La were four Sikorsky HOS-1 helicopters on loan from the Coast Guard. Their mission was to retrieve film from cameras in lead lined towers that would record the effects of the two atomic blasts of the Operation Crossroads atomic experiment. This small, hastily formed unit (technically not even a detachment since no Navy helicopter squadron yet existed) was under the charge of Navy CAPT Clayton Marcy, USN (helicopter pilot #7) and assisted by CDR Charles Wood, USNR (helicopter pilot #3), the only two pilots in this unit. Along with them were a small handful of maintainers that, for the most part, had never seen a helicopter up close before. Formed from Marcy’s own design, this was the Navy’s very first effort at integrating an operational helicopter unit aboard a ship and was the precursor to the Navy’s first helicopter squadron. Prior to this, Naval helicopter development, and all things required for it, belonged to the Coast Guard.

In November of 1941, the Coast Guard was essentially drafted into the Navy in anticipation of the US being drawn into WWII. Naturally, many of the duties assigned to Coast Guard aviation during the war involved coastal defense and lifesaving. As far as the Navy was concerned, this included countering the German u-boat crisis that was taking a heavy toll on merchant shipping far too close to home. Taking this charge to heart, it was a Coast Guard aviator named Frank Erickson that sold the idea of flying scouting helicopters off merchant ships to help fight the German u-boat scourge. On February 15, 1943, the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet issued a directive assigning responsibility for development of sea going helicopter operations to the United States Coast Guard. That July, CDR Marcy arrived at BuAer, joining a very small group of seasoned Naval Aviators assigned to the helicopter class desk, including CDR Wood. While the Navy had operational and administrative control over helicopter development during the war years, it was the Coast Guard that actually owned the Navy helicopters and trained the Navy the pilots and maintenance personnel. Both CAPT Marcy and CDR Wood were products of the Coast Guard helicopter pilot qualification course. After the war, CAPT Marcy was essentially left to build the Navy’s rotary wing future from the ground up, using whatever he could gather.

On January 6, 1946 the Coast Guard returned to the Treasury Department. Almost immediately afterward, they were underway on USS Midway (CVB-41) to support Operation Frostbite. Soon afterward, CAPT Marcy organized this Navy task unit for the atomic bomb tests at Bikini. The Coast Guard was already underway on Midway as CAPT Marcy loaded his men and equipment aboard Shangri La. As the Coast Guard was discovering on USS Midway, CAPT Marcy had several challenges ahead of him when it came to integrating helicopters into carrier flight operations. Among the biggest initial challenges was “spotting” the helicopters on the flight deck and in the hangar deck during flight operations. There was no blade fold mechanism on the HOS-1 so it commanded a full 48 feet in length from the forward tip of the main rotor to the aft most tip of the tail rotor. Additionally, the HOS-1 had a main rotor arc that spanned 38 feet. When these dimensions are multiplied by a factor of four, it adds up to a tremendous footprint for a flight deck crew tasked with conducting a full array of fixed-wing flight operations. The only solution was to remove at least two of the three main rotor blades from the HOS-1, dramatically reducing the footprint to just under 34 feet in length, by nine feet wide at the main mounts. The fuselage itself was less than four feet wide.

Unfortunately, a heavy fixed-wing flight schedule and the spotting challenges meant flying opportunities on the way to San Diego were essentially non-existent. There was one record setting flight however. On March 23, 1946, Shangri La transited the Panama Canal. It was during this transit that Marcy and Wood completed their only flight while enroute San Diego. Flying along the Panama Canal, the two completed the first-ever helicopter flight from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Shangri La arrived at Naval Air Station San Diego (now NAS North Island) a few days later. Now the Navy’s master helicopter base on the West Coast, home to 16 operational helicopter squadrons, the flights conducted there by CAPT Marcy and CDR Wood were the first pages in the long and proud history of Navy helicopters at North Island and the surrounding vicinity. Unfortunately, while in San Diego, CAPT Marcy personally logged what is likely the first mishap of a Navy helicopter flying out of NAS North Island.

Already an accomplished aviator, fresh from command of a combat squadron in the Pacific (VP-11) when he arrived at BuAer in 1943, CAPT Clayton Marcy completed his formal helicopter pilot training on October 10, 1945 through the Coast Guard training program. As the Navy’s highest ranking helicopter pilot, he was the most influential officer in the Navy when it came to Navy helicopter operational and organizational development. On April 11, 1946, CAPT Marcy departed NAS San Diego in HOS-1 BuNo 75616 on his initial solo in that model. He had logged a total of 3476.5 flight hours, which included 41 hours of rotary time; exactly 1.0 of that time was in the HOS-1. While conducting a practice autorotation at Sweetwater Airstrip, he flared too low and too sharply on recovery, causing a tail strike. CAPT Marcy was uninjured. Contrary to some accounts, the helicopter was badly damaged, but according to its aircraft history card, was not stricken as a result of the mishap and continued on the deployment.

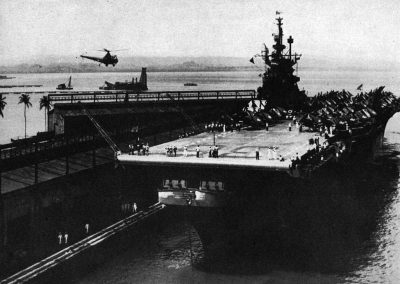

The four helicopters were transferred to USS Saidor (CVE-117) at San Diego and departed for Bikini on May 6, 1946. Saidor was the designated photographic ship for Operation Crossroads. Marcy and his helicopters were charged with the quick and expeditious recovery of film from cameras placed throughout the Bikini atomic test range documenting the destructive power of atomic weapons on Navy ships at various ranges and bringing it to Saidor for processing. Since x-rays emitted from an atomic blast were known to create a fog on film, some cameras close to the blast zone were to be placed in lead-lined towers. It was thought that the shipboard helicopter, which was used successfully by the USAAF to support B-29 maintenance (Operation Ivory Soap) and limited personnel recovery during the war could reach these remote locations and retrieve the film from the towers much more expediently than a small boat crew and thus reduce the time the film and personnel were exposed to a nuclear blast zone. There is also one account that discusses the helicopters ability to approach the impact zone at slow speeds with special equipment to ensure the radiation levels were safe for airplanes and surface craft. USS Saidor arrived at Bikini Atoll on May 24 and preparations for Operation Crossroads began in earnest. A week later, CAPT Marcy logged another mishap.

While attempting to takeoff from a confined area landing zone on Enyu Island at Bikini Atoll, CAPT Marcy (now with a total of 20 hours in model) experienced another tail strike. A little less than an hour earlier, he took off in HOS-1 BuNo 75598 from the deck of USS Saidor anchored in nearby Bikini Lagoon carrying Rear Admiral Frank Fahrion, Operation Crossroads task force commander, as his passenger and performed a routine landing in the clearing. Presently, he found himself in the unenviable position of being power limited in a confined area landing zone in a tropical environment during the summer months with the worst possible witness watching the whole situation unfold. Unable to hold a hover, the “soft ground and rough terrain” prevented any type of ground taxi to gain a bit more “runway” inside the landing zone and the trees in front of him, already blocking whatever wind nature provided, also prevented a running takeoff. On top of that, neither CAPT Marcy nor Admiral Fahrion could really be considered slight in build. It is not known whether Marcy made the decision himself or if the highly decorated future four star admiral provided “guidance”, but instead of reducing his gross weight by disembarking his passenger and relocating to a more suitable takeoff position, he attempted a series of what he described as “jump-takeoffs and short translational flights”. On the fourth of these jump take-offs, he struck the tail. Once again, while the damage was somewhat extensive, there were no injuries and the aircraft was repaired.

Three days later, CDR Wood departed USS Saidor in BuNo 75613 with a Navy captain named William Miller as a passenger on a mission to observe the Bikini Lagoon target array. After a little more than 30 minutes of routine flight, CDR Wood experienced a piece of his main rotor transmission “carry away”. When it did, it left behind an audible banging noise accompanied by vibration. He quickly noticed that his controllability was normal, but he was gradually losing altitude. From an altitude of about 200 feet he began his emergency approach to Saidor, which was at anchor only about 1500 yards away. The attempt was quickly abandoned in favor of a controlled ditch. As his altitude continued to bleed off, Wood turned into the wind. At approximately 2-3 ft, he pulled into the closest thing resembling a hover his helicopter would allow and advised CAPT Miller to dive out, which he did. As the helicopter settled into the water CDR Wood pushed his cyclic to the right (pilot side) to influence the direction his sinking helicopter would capsize, keeping the spinning rotor head away from the passenger while using seawater to bring it to a sudden stop. This allowed CDR Wood to quickly and safely dive out himself without fear of decapitation. Both the passenger and pilot were rescued by boat.

Thanks to a lot of quick thinking and sound judgement by CDR Wood, there were once again, no injuries. Like the rest of the helicopter pilots of the WWII years, CDR Wood was already an experienced Fleet Aviator prior to earning his helicopter pilot designation from the Coast Guard, which he did on September 26, 1944. At the time of the crash, CDR Wood had logged over 3300 flight hours. With 125 hours logged in the HOS-1 he was perhaps the most experienced pilot in model at the time. Also common for aviators of the time, he gained a lot of experience with mishap survivability during the years prior to his helicopter transition. This was the fourth recorded accident of his career. On this day, a failed clutch assembly was identified as the cause. BuNo 75613 was scrapped and an inspection of the clutch assemblies on all HOS-1 helicopters was recommended. Operation Crossroads continued. CAPT Marcy was down to three helicopters after only narrowly avoiding losing one a few days prior from his own tail strike and the first detonation of the atomic experiment was still almost a month away.

From a mechanical standpoint, the HOS-1 had a reputation for being very sound. Like all early helicopters, however, it was also somewhat frail and unforgiving. When the Coast Guard returned to the Treasury Department, much of the helicopter experience and limited airframe inventory acquired during WWII went with it. The HOS-1 faced a number of production challenges and delays during the war years and was manufactured in a very limited quantity. Of the just over 200 that rolled off the production line under license by Nash-Kelvinator, only 38 ever found their way to the Navy inventory, which at that time, really meant the Coast Guard. Spare parts for the HOS-1 were exceedingly rare. The Navy had almost no experience at maintaining helicopters and in the days before NATOPS, it was not uncommon for pilots to often familiarize themselves with pilot and airframe limitations of new models through “trial-and-error”. Procedures were not standard as understood today, but rather represented more of “best practice” that could actually vary from squadron to squadron. Maintenance and logistics challenges were no doubt anticipated, but things were already starting to add up very quickly.

Fortunately, the rest of the deployment was relatively uneventful regarding helicopter operations. Despite the obvious operational limitations, Navy helicopters did prove to be invaluable for transport, photography, observation, general utility, and radar calibration. On July 1st, the first atomic bomb of Operation Crossroads, historically recorded as “shot Able”, was detonated at Bikini. That same day, the Navy commissioned its first helicopter squadron, VX-3. Another product of CAPT Marcy’s visionary leadership in building a Navy rotary-wing community, the squadron stood up at Floyd Bennett Field under the command of CDR Charles Houston, USN (helicopter pilot #9). Tasked with the test and evaluation in the use of helicopters and their role in fleet operations, the squadron began with two qualified pilots, four HSN-1s and seven HOS-1s plucked from Coast Guard storage. They would quickly build the Naval helicopter community from the ground up using this first deployment as a cornerstone of the foundation.

The second and final detonation of Operation Crossroads, shot Baker, occurred on July 25, 1946, effectively concluding the atomic experiments at Bikini, and the Navy’s first helicopter deployment. USS Saidor departed Bikini on August 4th. Upon reaching San Diego, the three surviving helicopters were turned over to Carrier Air Service Unit 5 (CASU 5) on August 19, 1946 and disposed of a few months later as war surplus; listed as “stricken” by Coast Guard Headquarters on November 30, 1946. For CDR Wood, his time in the cockpit of a Navy helicopter seems to come to a close here as well. CAPT Marcy assumed command of VX-3 almost immediately upon his return from sea. While the lean Truman post-war drawdown years presented extreme fiscal challenges and legendary infighting amongst the services over budgetary table scraps, Navy rotary wing aviation rapidly expanded under his leadership. In just two years, with more capable equipment, a handful of skilled pilots, and a huge push from Sikorsky and other industry leaders of the day, Navy rotary-wing aviation quickly moved from an experiment to a fully formed, highly demanded fleet capability, largely based on its ability (or potential) to make fleet operations more efficient. In less than two years, he would go on to briefly command the Navy’s first operational helicopter squadron.