“MAYDAY” OVER NORTH KOREA”

– As written by USS IOWA helicopter pilot LT R.L. Dolton –

(Received from grandson Adam Dolton / with edits from Dave Way / IOWA’s Curator)

It was midafternoon July 15, 1952. I was flying over the coast of North Korea on a gun spotting mission with a Marine gunner in the rear seat. He held a chart showing the “coordinates” he used to direct gun fire from the battleship. Our mission was to find targets of opportunity to shoot at. The big 16 inch guns of the USS IOWA were directed by computers so as to automatically correct for ship movement and azimuth of the target. While thus engaged, the helicopter radio began receiving a “Mayday” call from a pilot who was “bailing out” over the mountains of North Korea. He gave his coordinates before jumping. He reported that he was flying an F4U Corsair Fighter and his engine had been hit by anti-aircraft fire near the target he was strafing. The message was also received by the IOWA and I was immediately recalled to base. Four rescue helicopters stationed at strategic points around Korea were always on guard duty. My helicopter, (a Sikorsky HO3S “Horse”), was one of the four and I was in the best location for this emergency. Upon landing back onboard, I learned that planes from the aircraft carrier USS PRINCETON were bombing and strafing bridges that crossed the YALU RIVER (northern border of Korea) in an effort to slow down the flow of Chinese crossing over from their base in China. LTJG H.A.Riedl of Boone, Iowa was one of those pilots.

In getting back to the ship, I instructed my crew to refuel and be ready for immediate takeoff. Captain Smedberg (Captain of the IOWA) informed me that Reidl’s Squadron Leader was in touch with the IOWA and wanted to attempt a rescue yet today if possible. Pilots of Reidl’s squadron were remaining on station to see where Reidl landed in his parachute. The planes were running low on fuel and the day was getting late with bad weather moving in. Could we do it? My answer was affirmative. I needed one crewman with a carbine semi-automatic rifle. Every man in my crew volunteered to go. I choose W.A. Meyer as he was the smallest and therefore the lightest in weight. Meyer was an ADI (mechanic) in case we went down and his light weight would mean more flying time over target if we had trouble finding our man.

Guided to the downed pilot’s location by his Squadron Leader flying an F4U Corsair, we arrived on location just at dusk. Reidl was using his walkie-talkie on the ground. He reported that he was OK, but the batteries were now very low and he was looking for a hiding place as troops were in the area. We could not see him, but thought he was about midway up the mountain. Darkness settled in quickly, so visibility was poor. The escorting planes reported that they were very low on fuel and had only enough to get back to their carrier some distance away. I was left alone to do what I could, which was nothing without backup guns to strafe while I attempted to land. And, of course I did not know his exact location. What to do!…..It did not take long to figure that I had better get out of those mountains before total darkness. The enemy would have probably been happy to tum on some lights for me to land by, but somehow it didn’t seem like the thing to do.

The battleship had rigged lights on the helicopter pad to aid in landing. It was just after dark when we touched down. I told Captain Smedberg that I would like to try again when the weather cleared somewhat. I checked the weather and went to bed.

About 4:30 AM next morning, a Marine guard was shaking me out of my sleep to inform me that the Captain was in touch with the PRINCETON and the Squadron Leader was willing to assist in another rescue attempt. The weather had now moved out to sea and engulfed the IOWA in heavy fog and light drizzle. The plan was that the Corsair would swing out of the clouds to our deck level and if I would lift off immediately, I could guide on his wings up through the clouds. The H03S helicopter we were flying did not have instrument capabilities, thus the need to use another airplane for an artificial horizon. We topped out at 4,000 feet and continued toward the target. The weather improved as we approached our location, but low lying clouds still hung like bed sheets between mountain peaks. The Squadron Leader’s code name was RED LEADER. Other fighter planes of the squadron were now on station to help. It was to be an all-out effort to get their pilot back to safety. “Red” Reidl had been on the ground all night and his radio was dead, so we did not know what we would find. Red Leader said he thought Reidl was under that cloud and gave me a reference as to which one. I flew over the spot, holding my altitude, as I did not want to commit too soon. I had seen a village nearby.

Then…directly in front of my helicopter a beautiful red flare rose majestically into the sky. The perfect timing of his shot and in the exact location, considering he could only hear the chopper and not see it, was an inspiration. I called Red Leader to advise that I was going under the clouds that hid our man from sight. The Squadron began to circle with guns “on ready” if strafing became an option. I could hear Meyer preparing his carbine for action. He had opened the sliding door and was ready and eager. The cloud was perched like a big white pancake between two rising peaks. The only place I could see to land near where I thought our pilot would be was on a slope between the two peaks. The ground was not flat enough to land so I knew I had to drive the nose of my helicopter into the sloping ground with wheels still in the air. Making sure the whirling blades above us did not touch the hill side was my only concern. Meyer was already firing at anything that moved. I carried a Smith and Wesson pistol but could not free my hands to fire. I was busy keeping the plane on the side of the hill. I heard Meyer cry out that troops were moving in as he grabbed for another can of ammo. Then, he said “I see him, he’s corning like a rabbit through the briar patch”. In an instant Red Reidl leaped through the open passenger door some 10 feet off the ground. “Get the hell out” he said, “there’re right behind me”.

I turned the helicopter as best I could by bumping it off the ground, as I had no lift from the chopper’s downwash. When on a slope the cushion of air normally formed by the rotor blades was slipping on down the slope. As I turned 180 degrees I could see troops coming up the slope from lower down. A few more bumps and the helicopter was air born. The choice was easy; I went up into the clouds which at that level was a very low ceiling. I flew horizontal in the thin cloud layer and broke out going north, but well below the surrounding mountain peaks. The Fighter Squadron was still circling to protect us as I headed west toward the open sea. There was still one more obstacle to face, however, and that was a narrow pass which we had to pass through as I climbed the helicopter to rise above the local terrain. As I entered the pass I was able to see a cliff on our port side with machine gun mounts in place. These guns opened fire as we approached. I could see the spark from the guns. Red Leader saw the guns at the same time as I requested help. The circling fighters came out of the sky like eagles diving for their prey. They hit the cliffs with 3 inch rockets and then followed up with another strafing pass. The cliff and its guns disappeared in a cloud of smoke and the helicopter passed through without further incident. Throughout the whole ordeal, both Meyer and Reidl were shooting out of both sides of the helicopter and only one side had a door. Reidl used his pistol, and Meyer kept the carbine hot. They were great!

When over water and safe from any unseen coastal guns, I headed the chopper south. I figured the battleship would be steaming north to intercept our position, but I was not sure how far north we were or where the ship would be. From our low altitude my line of sight to the horizon was about 20 miles. The battleship did not show up when I thought it should, so I called the Bridge to ask them to “blow out the stacks” so I could home in on the smoke as it rose into the air. The battleship was not familiar with this tactic, but pilots use it in flying from carriers when radio reception is bad. Soon a thin curl of smoke rose from over the horizon. It was beautiful, and we headed for home.

When “Red” Reidl stepped from the plane I noticed for the first time how covered he was with mud, even on his face and hands. He told us how it was on the ground as the press took notes for writing the story. He had heard his captors coming shortly after landing on the mountain side. His first inclination was to pull his revolver and shoot. Then he reasoned it would cost him his life and accomplish nothing. He then buried his parachute and then buried himself in the side of an old creek bed after covering himself with mud. He said during the night he could hear enemy troops talking on the trail above where he was hid. He remained there all night without food or drink. He was confident that his squadron would not abandon him and a helicopter would try for a rescue when daylight came. At daybreak he was alert and waiting. He could not see the helicopter but he listened to the sound above him and when he thought he had a fix on our position, he fired his only flare. If he had guessed wrong, or if he had fired behind us, we may not have been able to determine his position so accurately. Riedl had followed good training procedure and it probably saved his life.

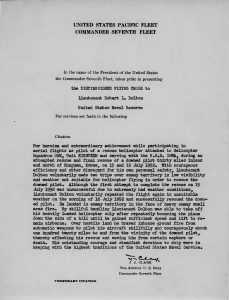

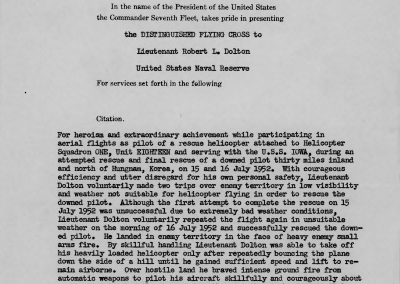

For this action my crewman ADI W.A. Meyer was awarded the Naval Air Metal, and I received the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross).