OLD NAVY ROTARY WING PICTURES-BRIAN MILLER COLLECTION

BRIAN MILLER COLLECTION-ABOUT THE COLLECTOR

Brian Miller is a retired West Coast LAMPS (SH-60B) pilot that became fascinated with the history of Naval Aviation, especially North Island. It all started by accident more than ten years ago when he came across a 100 year old picture of a forgotten San Diego aviation pioneer named Charles F. Walsh. This was his first purchase of a collection that has grown steadily ever since. Everything in his collection was purchased off the Internet. Many were candid photographs taken by amateurs and sold as part of an estate sale without much description. Some pictures of the collection are from the estate of Joe Rullo (helicopter pilot #17). They are all part of a growing collection that spans the 108 year history of Naval Aviation/North Island to include the evolution of the HSL/HSM community.

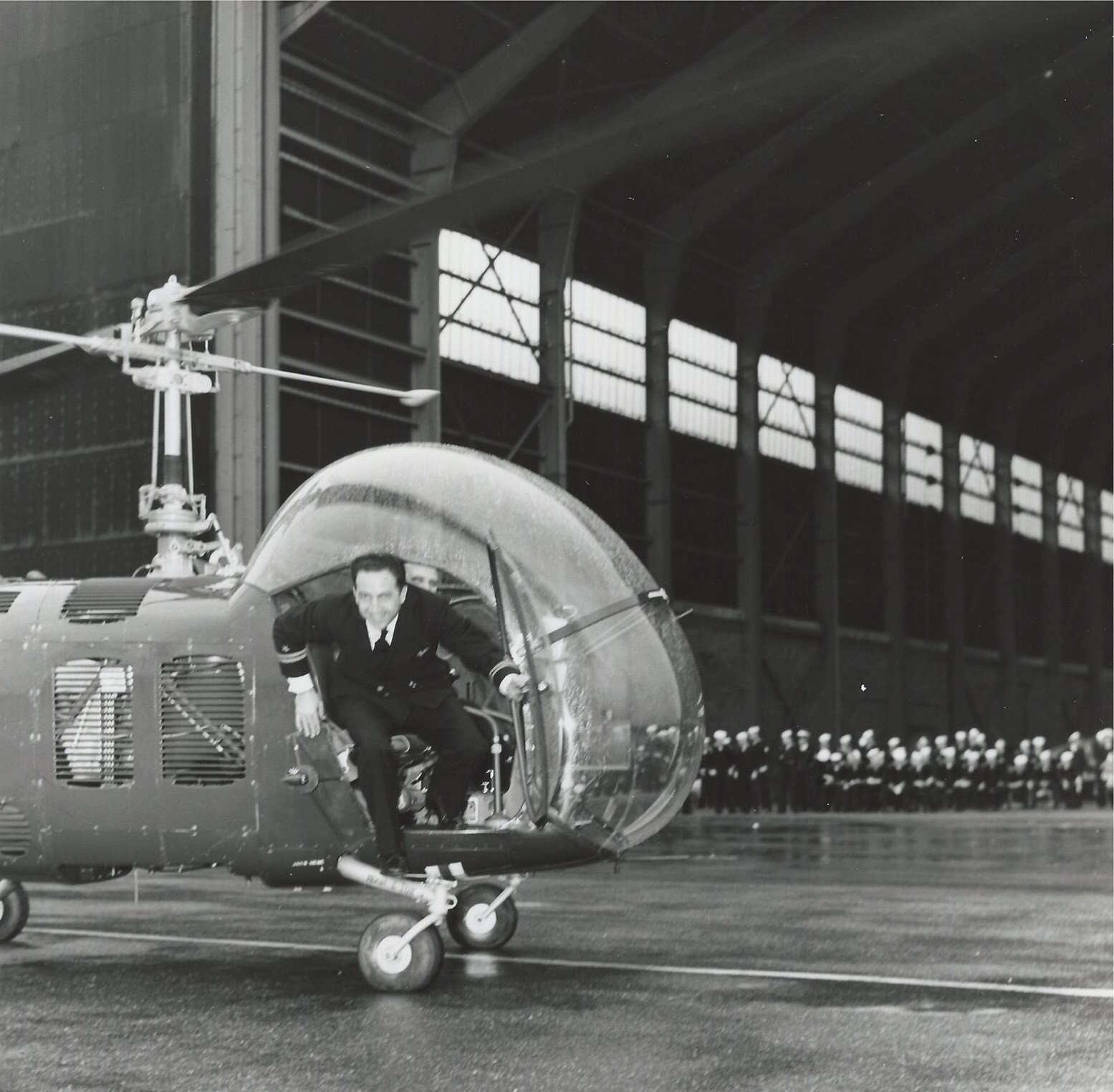

LT Joe Rullo (helicopter pilot #17),

August 16, 1948. LT Joe Rullo (helicopter pilot #17), pictured here exiting a Bell HTL-1, performed the first night flight in a helicopter on the West Coast (possibly anywhere). He and AD1 F. E. Asbell piloted one of two Bell HTL-1 helicopters that proved the concept of helicopter night flight during a two hour experiment over Kearney Mesa that night. Both helicopters were part of the newly formed HU-1 stationed at nearby NAAS Camp Miramar. At that time, West Coast rotary wing aviation consisted of a single squadron of 16 officer and 80 enlisted men operating HTL-1 and HO3S-1 helicopters.

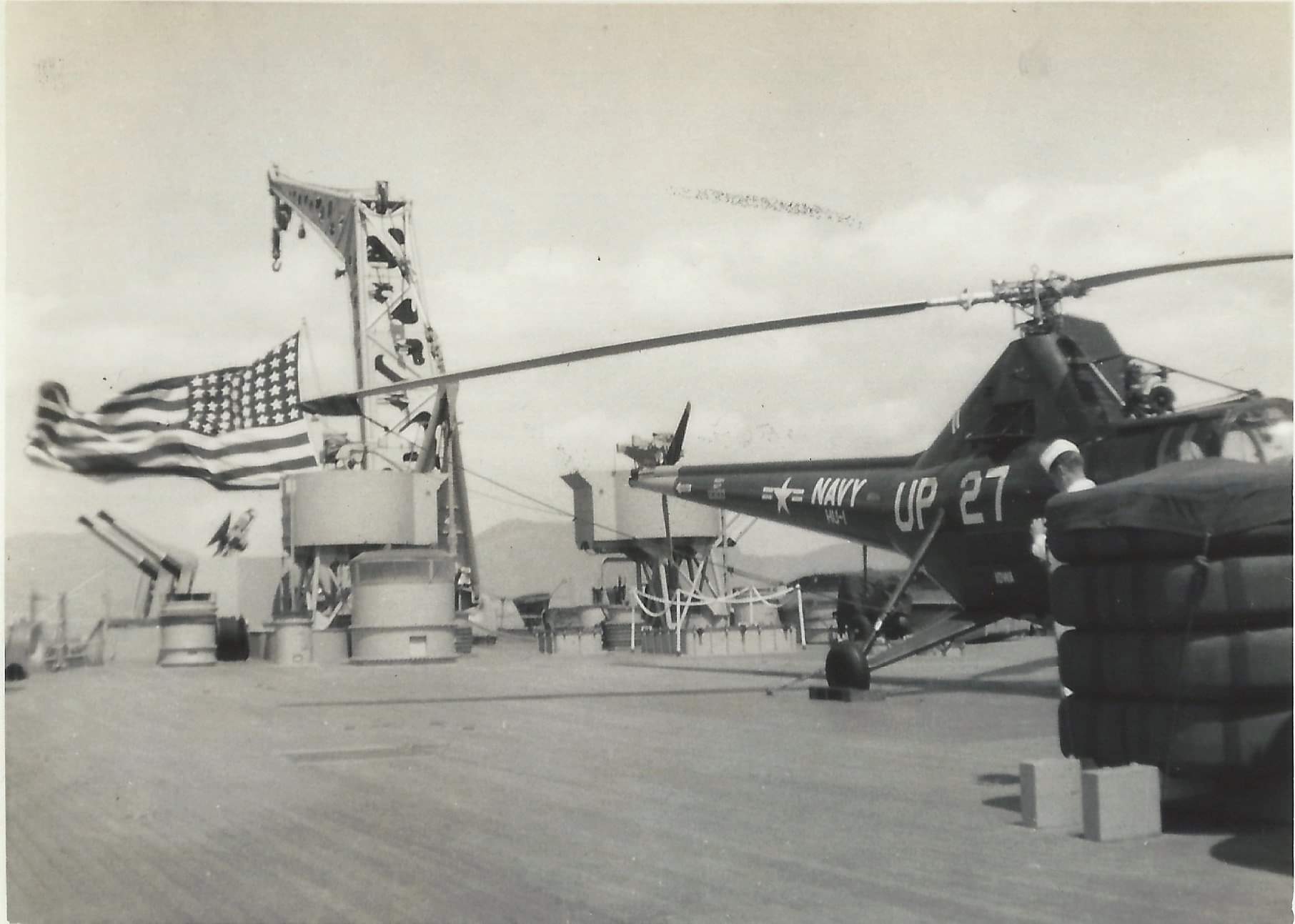

ussmisouri helo

Fantail of USS Missouri, probably during the Korean War. The immediate years following WWII were not kind to the battleship, or the helicopter for that matter. When the Korean War began, Big Mo was the only active battleship and that was only due to the political will of Harry Truman whose daughter christened the ship. During fleet maneuvers in 1947, Missouri’s gun turrets proved more than adequate as a temporary helipad to support helicopter logistics missions and even provided a life saving transport of their senior surgeon; doing in minutes what used to take hours. Scout planes were immediatley obsolete. Helicopters became operational in 1948 when VX-3 split into HU-1 and 2. By 1949, Missouri had both her seaplane catapults removed to make room for the helicopter. Helicopters such as this HO3S-1 from HU-2 out of NAS Lakehurst supplemented the already awesome lethality of the Iowa-class battleships during the Korean War by providing logistics, mine spotting, naval surface gunfire support (spotting) and SAR/MEDEVAC. These capabilities proved vital during the Korean War and Missouri was huge part in proving their concept before the conflict.

Helicopter pilot #750, AD1/AP William N. Longley,

Helicopter pilot #750, AD1/AP William N. Longley, about to board his HO3S-1 “Igor Beaver” aboard USS Saint Paul (CA-73), on 6 June 1953. He was just over two weeks shy of his 18th birthday when he enlisted in the Navy on December 14, 1942 out of Jacksonville, FL. Enlisting as a Soundman (Sonar Tech), Longley was a plankowner on two different minesweepers during the WWII. Following WWII, Longley earned an enlisted pilot rating at Corpus Christi, TX in 1947. At the outbreak of Korean War in 1950, the need for helicopter pilots intensified almost overnight. On February 20, 1952, AD1/AP Longley earned his helicopter pilot designation from HTU-1 (now HT-8) at Ellyson Field. At the time of this photo, he was reportedly one of only three enlisted helicopter pilots off Korea. In 2014, he passed away in Pensacola, FL at the age of 89. From his obituary: “Before retiring at the rank of Lt. Commander in 1972, Bill had a long and distinguished career as a military pilot with over 11,000 pilot hours. In 1962 he was awarded a commendation of the Streamlined Stork for having flown 27 different types of aircraft, including Fat Albert & Helicopters, between Pensacola and San Diego for a record 600,000 miles in 414 days without incident. It was the highest mileage ever recorded for that time. Bill served as a test pilot for the Naval Rework Facility at N.A.S[?] prior to his retirement. Bill received numerous medals including; (3) Good Conduct, American Theatre Area Ribbon, European African Middle East Ribbon, Air Medal, (2) WWII Victory Medal, Korean Service Medal & United Nations Medal.”

HU-1 Helo USS Iowa 1952

My photos of the Lucky Lady of HU-1 aboard USS Iowa, July 1952. The HO3S-1 pictured here proved to be an extremely capable multi-mission helicopter during this deployment. July of 1952 was a very active month on the gun line off the Korean Peninsula for USS Iowa and this detachment from the fleets first and only West Coast (San Diego) helo squadron provided aerial spotting for the shelling of Wonson and various other locations in direct support of UN forces. The month before, this aircrew rescued at least one downed aviator from the carrier Princeton. When HU-1 stood up at Miramar four years earlier, it consisted of about 18 pilots and a few helicopters. Almost immediately following the outbreak of war in Korea, demand for helicopter pilots swelled so dramatically that it gave rise to a dedicated training squadron that we know today at HT-8.

56196650_10215805630112467_7115435940910202880_n

On 1 April 1948, the helicopter development squadron formed on 1 July 1946 as VX-3 was disestablished at NAS Lakehurst, NJ. Simultaneously, the Navy commissioned its first two operational helicopter squadrons in its place. Both squadrons called themselves the “Fleet Angels” and were comprised largely of helicopters, officers, and men of the former VX-3 squadron. The ceremony was conducted adjacent to the historic Hangar 1 at NAS Lakehurst and was commemorated by the first mass formation flight of helicopters in history. HU-2, commanded by Captain Clayton Marcy (helicopter pilot #7), remained at NAS Lakehurst to train Navy and Marine Corps helicopter pilots and ground personnel as well as fulfill operational commitments to the fleet. Increased demand for helicopter pilots during the Korean War necessitated a dedicated training squadron. HTU-1 was established at Ellyson Field at Pensacola, FL on December 3, 1950 from elements of HU-2. This squadron became HT-8 on July 1, 1960, making them one of the two oldest helicopter squadrons in the Navy. Also on July 1, 1960, HU-2 was split to form HU-4. In time an HU-4 detachment at Norfolk grew large enough to become it’s own squadron and became HC-6. HC-6 was renamed HC-26 in 2005 and is still very much an active duty squadron on North Island today. 11 11 3 Comments Like Co

Nurses assigned to USS Haven (AH-12

Nurses assigned to USS Haven (AH-12) pose on helo deck. Korea, circa 1953. US Navy BUMED Photo # 16-0002-005, Coyle Collection. (Navsource, Michael G. Rhodes, BUMED)

HU-1 1948

On 1 April 1948, the helicopter development squadron formed on 1 July 1946 as VX-3 was disestablished at NAS Lakehurst, NJ. Simultaneously, the Navy commissioned its first two operational helicopter squadrons in its place. Both squadrons called themselves the “Fleet Angels” and were comprised largely of helicopters, officers, and men of the former VX-3 squadron. The ceremony was conducted adjacent to the historic Hangar 1 at NAS Lakehurst and was commemorated by the first mass formation flight of helicopters in history. HU-2, commanded by Captain Clayton Marcy (helicopter pilot #7), remained at NAS Lakehurst to train Navy and Marine Corps helicopter pilots and ground personnel as well as fulfill operational commitments to the fleet. Increased demand for helicopter pilots during the Korean War necessitated a dedicated training squadron. HTU-1 was established at Ellyson Field at Pensacola, FL on December 3, 1950 from elements of HU-2. This squadron became HT-8 on July 1, 1960, making them one of the two oldest helicopter squadrons in the Navy. Also on July 1, 1960, HU-2 was split to form HU-4. In time an HU-4 detachment at Norfolk grew large enough to become it’s own squadron and became HC-6. HC-6 was renamed HC-26 in 2005 and is still very much an active duty squadron on North Island today. 11 11 3 Comments Like Co

HU-1 1948 1b

On 1 April 1948, the helicopter development squadron formed on 1 July 1946 as VX-3 was disestablished at NAS Lakehurst, NJ. Simultaneously, the Navy commissioned its first two operational helicopter squadrons in its place. Both squadrons called themselves the “Fleet Angels” and were comprised largely of helicopters, officers, and men of the former VX-3 squadron. The ceremony was conducted adjacent to the historic Hangar 1 at NAS Lakehurst and was commemorated by the first mass formation flight of helicopters in history. HU-2, commanded by Captain Clayton Marcy (helicopter pilot #7), remained at NAS Lakehurst to train Navy and Marine Corps helicopter pilots and ground personnel as well as fulfill operational commitments to the fleet. Increased demand for helicopter pilots during the Korean War necessitated a dedicated training squadron. HTU-1 was established at Ellyson Field at Pensacola, FL on December 3, 1950 from elements of HU-2. This squadron became HT-8 on July 1, 1960, making them one of the two oldest helicopter squadrons in the Navy. Also on July 1, 1960, HU-2 was split to form HU-4. In time an HU-4 detachment at Norfolk grew large enough to become it’s own squadron and became HC-6. HC-6 was renamed HC-26 in 2005 and is still very much an active duty squadron on North Island today. 11 11 3 Comments Like Co

NAVT H-21 Aerial Minesweeping

March 19, 1955, location unknown. A Navy H-21 pulls a boat at a speed of 11 knots during a test demonstrating its ability to pull several times its load-lifting capacity. Following the Korean War, the Navy became very interested in the idea of using helicopters to overcome the limitations and vulnerabilities demonstrated by minesweepers and salvage vessels during that conflict and the H-21 delivered good results. By the time this picture was taken, the Navy had already successfully proven the ability of the H-21 as an aerial minesweeper to clear moored mines.

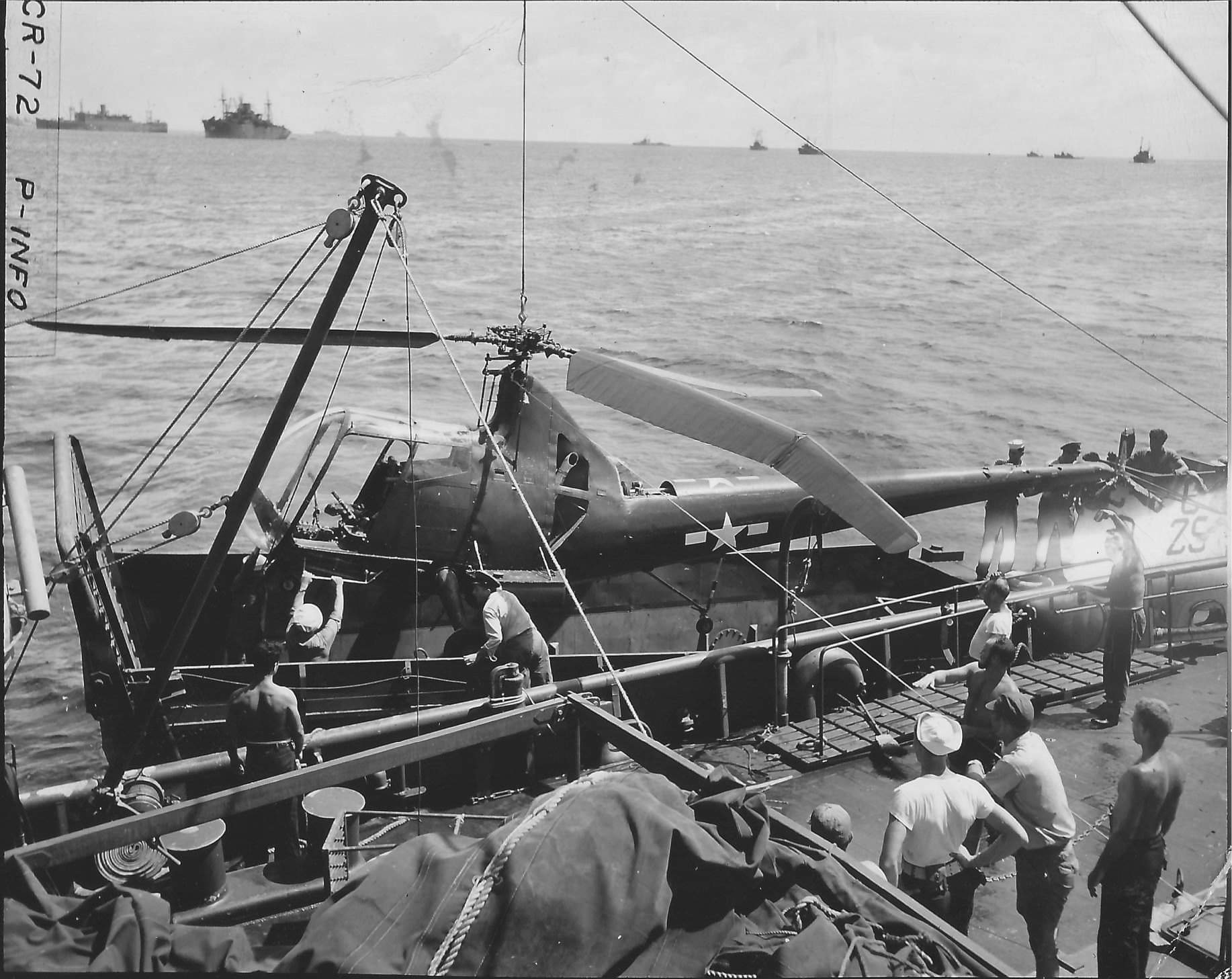

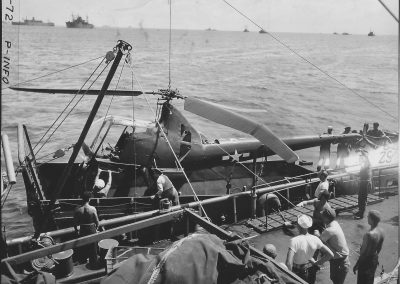

clayton Marcy Photos 1946a

July 1946. My photos of what is largely considered the first helicopter deployment in Naval History. Led by Captain Clayton Marcy (Helicopter Pilot #7), a detachment of four Sikorsky HOS-1 helicopters and support personnel embarked USS Saidor (CVE-117) to support Operation Crossroads. Along the way, Clayton Marcy became the first person to pilot a helicopter form the Atlantic to Pacific along the Panama Canal. Two of the helicopters were lost (apparently without injury) on the way to Bikini Atoll. For those who may not remember, Operation Crossroads was the atomic testing at Bikini Atoll. USS Saidor was the designated photo lab for the tests and the Navy helicopters were used to recover film from cameras that were otherwise inaccessible. Despite the loss of 50% of the aircraft, the mission was considered a success and Marcy went on to Command VX-3, the very first rotary wing test and evaluation squadron upon his return in 1946. He would later command HU-2 when it was formed from VX-3 in 1948. A better written version can be found on the link below under “Clayton Marcy”.

HC-4 Det 47 SH-2A Scooter 62

May 17, 1969, somewhere in the Mediterranean. Scooter 62 of HC-4 Det 47 flies above a pair of A-4 Skyhawks being serviced on USS Shangri La (CV-38). Scooter 62 was embarked on USS Little Rock (CLG-4), 6th Fleet flagship, for the 1968-69 deployment. HC-4 was located in hangar 4 at NAS Lakehurst, after splitting from HU-2 in 1960. In 1972, the squadron became HSL-30 and soon moved to Norfolk. Sometime after conversion to an SH-2F in 1974, the airframe depicted here as Scooter 62 was transferred to HSL-74.

HU-1 Det Helo USS Iowa 1b

My photos of the Lucky Lady of HU-1 aboard USS Iowa, July 1952. The HO3S-1 pictured here proved to be an extremely capable multi-mission helicopter during this deployment. July of 1952 was a very active month on the gun line off the Korean Peninsula for USS Iowa and this detachment from the fleets first and only West Coast (San Diego) helo squadron provided aerial spotting for the shelling of Wonson and various other locations in direct support of UN forces. The month before, this aircrew rescued at least one downed aviator from the carrier Princeton. When HU-1 stood up at Miramar four years earlier, it consisted of about 18 pilots and a few helicopters. Almost immediately following the outbreak of war in Korea, demand for helicopter pilots swelled so dramatically that it gave rise to a dedicated training squadron that we know today at HT-8.

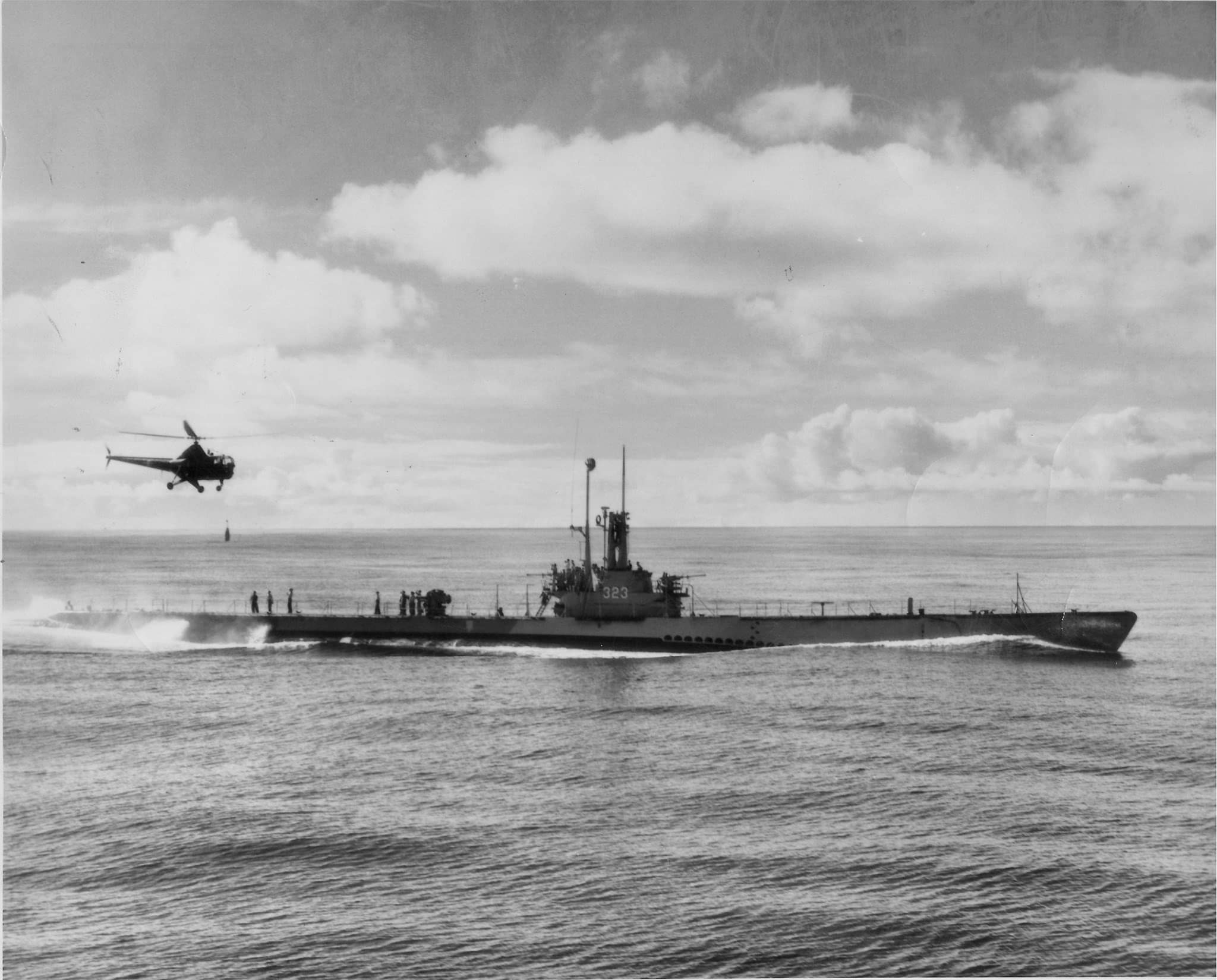

USS Corporal 1A

Another incredible story from the annals. To my knowledge, it has never been told in such detail before. If you enjoy this kind of storytelling, please check out our book! USS Corporal (SS-346): First Submarine To Reel in a Helicopter! By Charles G. Hood, MD On Thursday, 26 April 1956, off the southern coast of Florida about 20 miles from Key West, Cmdr. William F. Culley of Augusta, Georgia noticed a problem mid-flight. Culley, the pilot of Navy helicopter #51 on an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) training run as part of Squadron VX-1, realized that he was losing oil quickly from the main rotor assembly. He was too far from the coast to return for an emergency landing. Culley’s mind raced as he considered his options. Bailing was certainly possible, giving Culley and his three fellow crewmembers the best opportunity to survive the incident, although at the cost of a very expensive Navy helicopter—the Sikorsky HSS-1, known as the Seabat because of its ASW package. Finding a small cay in the vicinity to land on would be ideal, but a sweep of the ocean landscape failed to show any small land masses that might have provided such an opportunity. Crashing into the ocean was not a desirable option. Culley, his co-pilot Lt. J. K. Johnson, and two other crewmembers, G.A. DeChamp (SO3) and M.R. Dronz (AT2), realized that they had precious minutes to make a decision before mechanical failure required a costly abandonment. A “May-Day” call was sent from the helicopter in hopes that another Navy or even merchant vessel could lend a hand. Meanwhile, not far from the distressed chopper, the USS Corporal (SS-346), assigned to the submarine base at Key West, was submerged, also participating in the ASW exercises as a designated opposing boat. The Corporal was a Balao-class submarine. She was built at the Electric Boat shipyard in Groton, Connecticut and commissioned shortly after the conclusion of World War II in November 1945. She carried a complement of 10 officers and about 70 enlisted men. The Corporal was 312 feet in length with a beam of 27 feet, 3 inches. As it turned out, she would need every inch of that beam for her next unscheduled assignment. The radio shack of the Corporal intercepted the May-Day call from the disabled helicopter. This news was communicated immediately to the sub’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Erman O. Proctor in the Conn. He wasted little time. “Emergency surface. Blow all main ballast.” The words reverberated over the sub’s 1-MC as the Corporal executed an emergency blow and came to the surface with a gargantuan splash. In contact with the helicopter, Proctor ascertained that the chopper could remain airborne for only a short time longer. Culley requested the Corporal to make heavy knots in his direction to pick up survivors should the need to ditch the helicopter arise. The Corporal radioed that they were on their way to the scene directly and then proceeded at flank speed to the provided coordinates of the chopper. In just a few minutes, the Corporal made it first visual contact of the stationary chopper suspended only a short distance above the ocean surface. Moving in to the helicopter’s immediate vicinity, Proctor had an idea that he shared with Culley. “How about attempting an on-deck landing?” The reply from the chopper was emphatic: “Hell yes, let’s give it a go.” Absolutely no one wanted to see a valuable asset plunge needlessly to the ocean depths; the replacement price for the Sikorsky helicopter was about $250,000. The Corporal carefully positioned itself directly under the still-hovering helicopter. Communications between chopper and submarine continued at a fast and furious pace. The mechanical issue with the helicopter prevented it from turning in any direction; hovering was still functional, but no adjustment in heading could be made from the cockpit. Once the Corporal understood this problem, the submarine maneuvered herself in the open seas such that her after deck was lined up with the landing wheels of the chopper. But did the helicopter have enough room to land on the deck? There were two critical issues to ponder. First, was the beam of the submarine wide enough to accommodate the landing wheels of the helicopter? The answer to that question wasn’t immediately clear to those crewmembers of the Corporal who had gone topside to inspect the underside of the hovering helicopter. (The “recovery party” in this case consisted of volunteers headed up by the COB.) Second, assuming that there was enough room from side to side, could the pilot of the helicopter bring her down in the very tight window from fore to aft on the submarine deck without striking the sail with its main rotor or the fantail with its rear rotor? Since no one had ever seriously contemplated the answers to these questions, all the men could do was to look closely and guess. To all who were there, it seemed like a very tight proposition, but there seemed to be just enough room from fore to aft and from port to starboard along the after deck to give it a shot. Still, given the vagaries of the sea and wind conditions that could shift the relative positions of the submarine and helicopter, the whole idea was incredibly risky. However, short of dumping the chopper there seemed to be no other viable alternatives, so the submarine crew prepared for the surprise drop-in. The COB and his topside men had no protocol manual to draw from. They simply relied on their instincts and collective ingenuity to mitigate the risks of the impending landing—such as taking down the long wire antenna to avoid an inadvertent snag. The men then grabbed mooring lines in preparation for the next step. The helicopter began its final descent as pilot Culley attempted to keep his bird directly over the centerline of the submarine hull. Except for one intrepid sailor, the members of the recovery party stayed crouched at a safe distance just forward of the sail during this time. The person who volunteered to remain in harm’s way was engineering officer LTJG George Ellis, who braced himself along the after edge of the sail and provided hand signals for the pilot to fine-tune his landing. Ellis’ role was critical as the margin for error was razor-thin. He risked serious injury or even death from any errant move during his makeshift role as a signal officer, as the main rotor blades of the descending helicopter spun very close to his head. The radio shack of the sub sent the message, “Do you think you will make it?” Any response from the helicopter was delayed, since the message was received just as the three wheels of the chopper (2 front, 1 rear) made contact with the weather deck. The landing had to be absolutely perfect, and fortunately the seas had become mercifully calm during the attempt. With the precise teamwork between the hand signals of LTJG Ellis and the considerable skill of the chopper pilot, the bird miraculously touched down. Incredibly, a small part of each front wheel ended up overhanging the deck edge on each side, but there was just enough room for most of the rubber for the helicopter to remain stable topside. The men on board estimated that an inch or two longer span on the landing gear would have made the attempt a no-go. “We’re on your deck and damn happy to be here!”, came the relieved reply from the helicopter. The pilot had stuck the landing on the very first try. The recovery party rushed over with their mooring lines to tie up the chopper to the submarine. It was the first time that a submarine had ever rescued a helicopter, and it was entirely coincidental (and fortuitous) that the width of the submarine deck was just enough to accommodate the chopper’s landing gear. Once the blades of the helicopter had spun to a complete stop and the assembly was properly secured, the crew emerged onto the deck, where they were met by Lt. Cmdr. Proctor. “Welcome aboard!”, offered the skipper, in perhaps one of the most unusual unplanned visits in submarine history. The guests were escorted down the hatch and offered food and drink, while the Corporal steamed back to the Naval Annex at Key West, arriving just before sunset around 1830 hours local time. Word had spread about the plight of the helicopter and the unconventional heroism aboard the Corporal that had saved her; as a result, a large crowd had gathered spontaneously at the pier to greet both submarine and helicopter. It must have been quite a curious sight to witness the sleek submarine heading into her berth with the most unlikely bounty lashed to her dorsal hull. Navy mechanics made the necessary repairs to the helicopter after a large crane lifted the bird from its precipitous perch on the Corporal. The broken oil casing on the rotor was replaced, and the chopper again was ready for flight. Subsequently, the four-man crew climbed back into the cabin to depart, after grateful handshakes had been exchanged all around. Giving the thumbs up, Cmdr. Culley started the main engine, and those assembled at the pier to see the chopper off held onto their hats as the big bird took to the sky. In minutes, the helicopter was out of sight, and the men of the Corporal had themselves the yarn of a lifetime—about the big one that didn’t get away. My thanks to the members of the Poopie Suits and Cowboy Boots advisory board who contributed in various ways to the final product.

USS Corporal 1c

Another incredible story from the annals. To my knowledge, it has never been told in such detail before. If you enjoy this kind of storytelling, please check out our book! USS Corporal (SS-346): First Submarine To Reel in a Helicopter! By Charles G. Hood, MD On Thursday, 26 April 1956, off the southern coast of Florida about 20 miles from Key West, Cmdr. William F. Culley of Augusta, Georgia noticed a problem mid-flight. Culley, the pilot of Navy helicopter #51 on an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) training run as part of Squadron VX-1, realized that he was losing oil quickly from the main rotor assembly. He was too far from the coast to return for an emergency landing. Culley’s mind raced as he considered his options. Bailing was certainly possible, giving Culley and his three fellow crewmembers the best opportunity to survive the incident, although at the cost of a very expensive Navy helicopter—the Sikorsky HSS-1, known as the Seabat because of its ASW package. Finding a small cay in the vicinity to land on would be ideal, but a sweep of the ocean landscape failed to show any small land masses that might have provided such an opportunity. Crashing into the ocean was not a desirable option. Culley, his co-pilot Lt. J. K. Johnson, and two other crewmembers, G.A. DeChamp (SO3) and M.R. Dronz (AT2), realized that they had precious minutes to make a decision before mechanical failure required a costly abandonment. A “May-Day” call was sent from the helicopter in hopes that another Navy or even merchant vessel could lend a hand. Meanwhile, not far from the distressed chopper, the USS Corporal (SS-346), assigned to the submarine base at Key West, was submerged, also participating in the ASW exercises as a designated opposing boat. The Corporal was a Balao-class submarine. She was built at the Electric Boat shipyard in Groton, Connecticut and commissioned shortly after the conclusion of World War II in November 1945. She carried a complement of 10 officers and about 70 enlisted men. The Corporal was 312 feet in length with a beam of 27 feet, 3 inches. As it turned out, she would need every inch of that beam for her next unscheduled assignment. The radio shack of the Corporal intercepted the May-Day call from the disabled helicopter. This news was communicated immediately to the sub’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Erman O. Proctor in the Conn. He wasted little time. “Emergency surface. Blow all main ballast.” The words reverberated over the sub’s 1-MC as the Corporal executed an emergency blow and came to the surface with a gargantuan splash. In contact with the helicopter, Proctor ascertained that the chopper could remain airborne for only a short time longer. Culley requested the Corporal to make heavy knots in his direction to pick up survivors should the need to ditch the helicopter arise. The Corporal radioed that they were on their way to the scene directly and then proceeded at flank speed to the provided coordinates of the chopper. In just a few minutes, the Corporal made it first visual contact of the stationary chopper suspended only a short distance above the ocean surface. Moving in to the helicopter’s immediate vicinity, Proctor had an idea that he shared with Culley. “How about attempting an on-deck landing?” The reply from the chopper was emphatic: “Hell yes, let’s give it a go.” Absolutely no one wanted to see a valuable asset plunge needlessly to the ocean depths; the replacement price for the Sikorsky helicopter was about $250,000. The Corporal carefully positioned itself directly under the still-hovering helicopter. Communications between chopper and submarine continued at a fast and furious pace. The mechanical issue with the helicopter prevented it from turning in any direction; hovering was still functional, but no adjustment in heading could be made from the cockpit. Once the Corporal understood this problem, the submarine maneuvered herself in the open seas such that her after deck was lined up with the landing wheels of the chopper. But did the helicopter have enough room to land on the deck? There were two critical issues to ponder. First, was the beam of the submarine wide enough to accommodate the landing wheels of the helicopter? The answer to that question wasn’t immediately clear to those crewmembers of the Corporal who had gone topside to inspect the underside of the hovering helicopter. (The “recovery party” in this case consisted of volunteers headed up by the COB.) Second, assuming that there was enough room from side to side, could the pilot of the helicopter bring her down in the very tight window from fore to aft on the submarine deck without striking the sail with its main rotor or the fantail with its rear rotor? Since no one had ever seriously contemplated the answers to these questions, all the men could do was to look closely and guess. To all who were there, it seemed like a very tight proposition, but there seemed to be just enough room from fore to aft and from port to starboard along the after deck to give it a shot. Still, given the vagaries of the sea and wind conditions that could shift the relative positions of the submarine and helicopter, the whole idea was incredibly risky. However, short of dumping the chopper there seemed to be no other viable alternatives, so the submarine crew prepared for the surprise drop-in. The COB and his topside men had no protocol manual to draw from. They simply relied on their instincts and collective ingenuity to mitigate the risks of the impending landing—such as taking down the long wire antenna to avoid an inadvertent snag. The men then grabbed mooring lines in preparation for the next step. The helicopter began its final descent as pilot Culley attempted to keep his bird directly over the centerline of the submarine hull. Except for one intrepid sailor, the members of the recovery party stayed crouched at a safe distance just forward of the sail during this time. The person who volunteered to remain in harm’s way was engineering officer LTJG George Ellis, who braced himself along the after edge of the sail and provided hand signals for the pilot to fine-tune his landing. Ellis’ role was critical as the margin for error was razor-thin. He risked serious injury or even death from any errant move during his makeshift role as a signal officer, as the main rotor blades of the descending helicopter spun very close to his head. The radio shack of the sub sent the message, “Do you think you will make it?” Any response from the helicopter was delayed, since the message was received just as the three wheels of the chopper (2 front, 1 rear) made contact with the weather deck. The landing had to be absolutely perfect, and fortunately the seas had become mercifully calm during the attempt. With the precise teamwork between the hand signals of LTJG Ellis and the considerable skill of the chopper pilot, the bird miraculously touched down. Incredibly, a small part of each front wheel ended up overhanging the deck edge on each side, but there was just enough room for most of the rubber for the helicopter to remain stable topside. The men on board estimated that an inch or two longer span on the landing gear would have made the attempt a no-go. “We’re on your deck and damn happy to be here!”, came the relieved reply from the helicopter. The pilot had stuck the landing on the very first try. The recovery party rushed over with their mooring lines to tie up the chopper to the submarine. It was the first time that a submarine had ever rescued a helicopter, and it was entirely coincidental (and fortuitous) that the width of the submarine deck was just enough to accommodate the chopper’s landing gear. Once the blades of the helicopter had spun to a complete stop and the assembly was properly secured, the crew emerged onto the deck, where they were met by Lt. Cmdr. Proctor. “Welcome aboard!”, offered the skipper, in perhaps one of the most unusual unplanned visits in submarine history. The guests were escorted down the hatch and offered food and drink, while the Corporal steamed back to the Naval Annex at Key West, arriving just before sunset around 1830 hours local time. Word had spread about the plight of the helicopter and the unconventional heroism aboard the Corporal that had saved her; as a result, a large crowd had gathered spontaneously at the pier to greet both submarine and helicopter. It must have been quite a curious sight to witness the sleek submarine heading into her berth with the most unlikely bounty lashed to her dorsal hull. Navy mechanics made the necessary repairs to the helicopter after a large crane lifted the bird from its precipitous perch on the Corporal. The broken oil casing on the rotor was replaced, and the chopper again was ready for flight. Subsequently, the four-man crew climbed back into the cabin to depart, after grateful handshakes had been exchanged all around. Giving the thumbs up, Cmdr. Culley started the main engine, and those assembled at the pier to see the chopper off held onto their hats as the big bird took to the sky. In minutes, the helicopter was out of sight, and the men of the Corporal had themselves the yarn of a lifetime—about the big one that didn’t get away. My thanks to the members of the Poopie Suits and Cowboy Boots advisory board who contributed in various ways to the final product.

clayton Marcy 1b

July 1946. My photos of what is largely considered the first helicopter deployment in Naval History. Led by Captain Clayton Marcy (Helicopter Pilot #7), a detachment of four Sikorsky HOS-1 helicopters and support personnel embarked USS Saidor (CVE-117) to support Operation Crossroads. Along the way, Clayton Marcy became the first person to pilot a helicopter form the Atlantic to Pacific along the Panama Canal. Two of the helicopters were lost (apparently without injury) on the way to Bikini Atoll. For those who may not remember, Operation Crossroads was the atomic testing at Bikini Atoll. USS Saidor was the designated photo lab for the tests and the Navy helicopters were used to recover film from cameras that were otherwise inaccessible. Despite the loss of 50% of the aircraft, the mission was considered a success and Marcy went on to Command VX-3, the very first rotary wing test and evaluation squadron upon his return in 1946. He would later command HU-2 when it was formed from VX-3 in 1948. A better written version can be found on the link below under “Clayton Marcy”.

Clayton Marcy 1c

July 1946. My photos of what is largely considered the first helicopter deployment in Naval History. Led by Captain Clayton Marcy (Helicopter Pilot #7), a detachment of four Sikorsky HOS-1 helicopters and support personnel embarked USS Saidor (CVE-117) to support Operation Crossroads. Along the way, Clayton Marcy became the first person to pilot a helicopter form the Atlantic to Pacific along the Panama Canal. Two of the helicopters were lost (apparently without injury) on the way to Bikini Atoll. For those who may not remember, Operation Crossroads was the atomic testing at Bikini Atoll. USS Saidor was the designated photo lab for the tests and the Navy helicopters were used to recover film from cameras that were otherwise inaccessible. Despite the loss of 50% of the aircraft, the mission was considered a success and Marcy went on to Command VX-3, the very first rotary wing test and evaluation squadron upon his return in 1946. He would later command HU-2 when it was formed from VX-3 in 1948. A better written version can be found on the link below under “Clayton Marcy”.

Clayton Marcy 1d

July 1946. My photos of what is largely considered the first helicopter deployment in Naval History. Led by Captain Clayton Marcy (Helicopter Pilot #7), a detachment of four Sikorsky HOS-1 helicopters and support personnel embarked USS Saidor (CVE-117) to support Operation Crossroads. Along the way, Clayton Marcy became the first person to pilot a helicopter form the Atlantic to Pacific along the Panama Canal. Two of the helicopters were lost (apparently without injury) on the way to Bikini Atoll. For those who may not remember, Operation Crossroads was the atomic testing at Bikini Atoll. USS Saidor was the designated photo lab for the tests and the Navy helicopters were used to recover film from cameras that were otherwise inaccessible. Despite the loss of 50% of the aircraft, the mission was considered a success and Marcy went on to Command VX-3, the very first rotary wing test and evaluation squadron upon his return in 1946. He would later command HU-2 when it was formed from VX-3 in 1948. A better written version can be found on the link below under “Clayton Marcy”.

HU-1 1948 1c

On 1 April 1948, the helicopter development squadron formed on 1 July 1946 as VX-3 was disestablished at NAS Lakehurst, NJ. Simultaneously, the Navy commissioned its first two operational helicopter squadrons in its place. Both squadrons called themselves the “Fleet Angels” and were comprised largely of helicopters, officers, and men of the former VX-3 squadron. The ceremony was conducted adjacent to the historic Hangar 1 at NAS Lakehurst and was commemorated by the first mass formation flight of helicopters in history. HU-2, commanded by Captain Clayton Marcy (helicopter pilot #7), remained at NAS Lakehurst to train Navy and Marine Corps helicopter pilots and ground personnel as well as fulfill operational commitments to the fleet. Increased demand for helicopter pilots during the Korean War necessitated a dedicated training squadron. HTU-1 was established at Ellyson Field at Pensacola, FL on December 3, 1950 from elements of HU-2. This squadron became HT-8 on July 1, 1960, making them one of the two oldest helicopter squadrons in the Navy. Also on July 1, 1960, HU-2 was split to form HU-4. In time an HU-4 detachment at Norfolk grew large enough to become it’s own squadron and became HC-6. HC-6 was renamed HC-26 in 2005 and is still very much an active duty squadron on North Island today. 11 11 3 Comments Like Co

Helicopter pilot #750, AD1/AP William N. Longley

Helicopter pilot #750, AD1/AP William N. Longley, about to board his HO3S-1 “Igor Beaver” aboard USS Saint Paul (CA-73), on 6 June 1953. He was just over two weeks shy of his 18th birthday when he enlisted in the Navy on December 14, 1942 out of Jacksonville, FL. Enlisting as a Soundman (Sonar Tech), Longley was a plankowner on two different minesweepers during the WWII.

USS Corporal 1b

Another incredible story from the annals. To my knowledge, it has never been told in such detail before. If you enjoy this kind of storytelling, please check out our book! USS Corporal (SS-346): First Submarine To Reel in a Helicopter! By Charles G. Hood, MD On Thursday, 26 April 1956, off the southern coast of Florida about 20 miles from Key West, Cmdr. William F. Culley of Augusta, Georgia noticed a problem mid-flight. Culley, the pilot of Navy helicopter #51 on an antisubmarine warfare (ASW) training run as part of Squadron VX-1, realized that he was losing oil quickly from the main rotor assembly. He was too far from the coast to return for an emergency landing. Culley’s mind raced as he considered his options. Bailing was certainly possible, giving Culley and his three fellow crewmembers the best opportunity to survive the incident, although at the cost of a very expensive Navy helicopter—the Sikorsky HSS-1, known as the Seabat because of its ASW package. Finding a small cay in the vicinity to land on would be ideal, but a sweep of the ocean landscape failed to show any small land masses that might have provided such an opportunity. Crashing into the ocean was not a desirable option. Culley, his co-pilot Lt. J. K. Johnson, and two other crewmembers, G.A. DeChamp (SO3) and M.R. Dronz (AT2), realized that they had precious minutes to make a decision before mechanical failure required a costly abandonment. A “May-Day” call was sent from the helicopter in hopes that another Navy or even merchant vessel could lend a hand. Meanwhile, not far from the distressed chopper, the USS Corporal (SS-346), assigned to the submarine base at Key West, was submerged, also participating in the ASW exercises as a designated opposing boat. The Corporal was a Balao-class submarine. She was built at the Electric Boat shipyard in Groton, Connecticut and commissioned shortly after the conclusion of World War II in November 1945. She carried a complement of 10 officers and about 70 enlisted men. The Corporal was 312 feet in length with a beam of 27 feet, 3 inches. As it turned out, she would need every inch of that beam for her next unscheduled assignment. The radio shack of the Corporal intercepted the May-Day call from the disabled helicopter. This news was communicated immediately to the sub’s skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Erman O. Proctor in the Conn. He wasted little time. “Emergency surface. Blow all main ballast.” The words reverberated over the sub’s 1-MC as the Corporal executed an emergency blow and came to the surface with a gargantuan splash. In contact with the helicopter, Proctor ascertained that the chopper could remain airborne for only a short time longer. Culley requested the Corporal to make heavy knots in his direction to pick up survivors should the need to ditch the helicopter arise. The Corporal radioed that they were on their way to the scene directly and then proceeded at flank speed to the provided coordinates of the chopper. In just a few minutes, the Corporal made it first visual contact of the stationary chopper suspended only a short distance above the ocean surface. Moving in to the helicopter’s immediate vicinity, Proctor had an idea that he shared with Culley. “How about attempting an on-deck landing?” The reply from the chopper was emphatic: “Hell yes, let’s give it a go.” Absolutely no one wanted to see a valuable asset plunge needlessly to the ocean depths; the replacement price for the Sikorsky helicopter was about $250,000. The Corporal carefully positioned itself directly under the still-hovering helicopter. Communications between chopper and submarine continued at a fast and furious pace. The mechanical issue with the helicopter prevented it from turning in any direction; hovering was still functional, but no adjustment in heading could be made from the cockpit. Once the Corporal understood this problem, the submarine maneuvered herself in the open seas such that her after deck was lined up with the landing wheels of the chopper. But did the helicopter have enough room to land on the deck? There were two critical issues to ponder. First, was the beam of the submarine wide enough to accommodate the landing wheels of the helicopter? The answer to that question wasn’t immediately clear to those crewmembers of the Corporal who had gone topside to inspect the underside of the hovering helicopter. (The “recovery party” in this case consisted of volunteers headed up by the COB.) Second, assuming that there was enough room from side to side, could the pilot of the helicopter bring her down in the very tight window from fore to aft on the submarine deck without striking the sail with its main rotor or the fantail with its rear rotor? Since no one had ever seriously contemplated the answers to these questions, all the men could do was to look closely and guess. To all who were there, it seemed like a very tight proposition, but there seemed to be just enough room from fore to aft and from port to starboard along the after deck to give it a shot. Still, given the vagaries of the sea and wind conditions that could shift the relative positions of the submarine and helicopter, the whole idea was incredibly risky. However, short of dumping the chopper there seemed to be no other viable alternatives, so the submarine crew prepared for the surprise drop-in. The COB and his topside men had no protocol manual to draw from. They simply relied on their instincts and collective ingenuity to mitigate the risks of the impending landing—such as taking down the long wire antenna to avoid an inadvertent snag. The men then grabbed mooring lines in preparation for the next step. The helicopter began its final descent as pilot Culley attempted to keep his bird directly over the centerline of the submarine hull. Except for one intrepid sailor, the members of the recovery party stayed crouched at a safe distance just forward of the sail during this time. The person who volunteered to remain in harm’s way was engineering officer LTJG George Ellis, who braced himself along the after edge of the sail and provided hand signals for the pilot to fine-tune his landing. Ellis’ role was critical as the margin for error was razor-thin. He risked serious injury or even death from any errant move during his makeshift role as a signal officer, as the main rotor blades of the descending helicopter spun very close to his head. The radio shack of the sub sent the message, “Do you think you will make it?” Any response from the helicopter was delayed, since the message was received just as the three wheels of the chopper (2 front, 1 rear) made contact with the weather deck. The landing had to be absolutely perfect, and fortunately the seas had become mercifully calm during the attempt. With the precise teamwork between the hand signals of LTJG Ellis and the considerable skill of the chopper pilot, the bird miraculously touched down. Incredibly, a small part of each front wheel ended up overhanging the deck edge on each side, but there was just enough room for most of the rubber for the helicopter to remain stable topside. The men on board estimated that an inch or two longer span on the landing gear would have made the attempt a no-go. “We’re on your deck and damn happy to be here!”, came the relieved reply from the helicopter. The pilot had stuck the landing on the very first try. The recovery party rushed over with their mooring lines to tie up the chopper to the submarine. It was the first time that a submarine had ever rescued a helicopter, and it was entirely coincidental (and fortuitous) that the width of the submarine deck was just enough to accommodate the chopper’s landing gear. Once the blades of the helicopter had spun to a complete stop and the assembly was properly secured, the crew emerged onto the deck, where they were met by Lt. Cmdr. Proctor. “Welcome aboard!”, offered the skipper, in perhaps one of the most unusual unplanned visits in submarine history. The guests were escorted down the hatch and offered food and drink, while the Corporal steamed back to the Naval Annex at Key West, arriving just before sunset around 1830 hours local time. Word had spread about the plight of the helicopter and the unconventional heroism aboard the Corporal that had saved her; as a result, a large crowd had gathered spontaneously at the pier to greet both submarine and helicopter. It must have been quite a curious sight to witness the sleek submarine heading into her berth with the most unlikely bounty lashed to her dorsal hull. Navy mechanics made the necessary repairs to the helicopter after a large crane lifted the bird from its precipitous perch on the Corporal. The broken oil casing on the rotor was replaced, and the chopper again was ready for flight. Subsequently, the four-man crew climbed back into the cabin to depart, after grateful handshakes had been exchanged all around. Giving the thumbs up, Cmdr. Culley started the main engine, and those assembled at the pier to see the chopper off held onto their hats as the big bird took to the sky. In minutes, the helicopter was out of sight, and the men of the Corporal had themselves the yarn of a lifetime—about the big one that didn’t get away. My thanks to the members of the Poopie Suits and Cowboy Boots advisory board who contributed in various ways to the final product.

HUP Retreiver Norfolk

HUP-1 Retriever on the ramp at NAS Norfolk, Breezy Point Seaplane Base in March 1952. The “UR” tailcode denotes this helicopter belongs to HU-2 of NAS Lakehurst.

Marine Corps H-34

Marine Corps H-34 from (what I believe to be) the “Lucky Red Lions” of HMM-363 aboard USS Repose (AH-16) off Vietnam, sometime between 1965 and 1968. The squadron was activated on June 2, 1952 as HMR-363 to meet the demands of the Korean War and has been active ever since. They became the first West Coast squadron to transition to the H-34 from the HRS-1 and became HMM-363. In 1969, the squadron transitioned to the MH-53A and was renamed HMH-363. Since 2012, the “Lucky Red Lions” have flown the MV-22 Osprey as VMM-363.

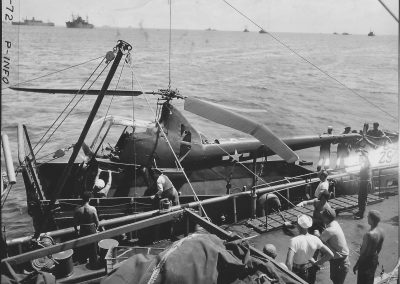

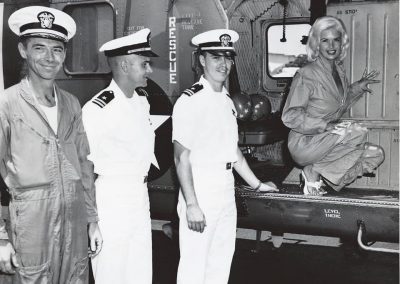

Jane Mansfield H-34 Seabat Helicopter 1960-61

Jayne Mansfield in the cabin of what appears to be an SH-34G or J (HSS-1 prior to 1962) Seabat ASW helicopter, date and location unknown. This was probably during a USO tour, possibly at Newfoundland around 1961 or 1962.

Joellen Drag, First Navy Female Helicopter Pilot

ENS Joellen Drag, the Navy’s first female helicopter pilot, in the cockpit of a CH-46 on the HC-3 flight line on NAS North Island in May of 1974. At the time, women were not allowed to hover over the flight deck of a seagoing ship, let alone land. Failing to get permission through her proper chain of command, Drag pursued additional avenues. In 1977 she was part of a successful class action lawsuit against the Navy. In the fall of 1978, Congress drafted new legislation allowing women to be assigned to shipboard billets. Joellen Drag-Oslund went on to have a successful career with the Navy, eventually retiring as a Captain.

HU-1 commissioning 1948 1a

15 May 1948. Commissioned at NAS Lakehurst, NJ on 1 April, 1948, the Navy’s first West Coast helicopter squadron opened for business at their new home at NAAF Miramar, CA. The original “Fleet Angels” of Helicopter Utility Squadron One (HU-1) consisted of 16 officers, 80 enlisted men, and a handful of Bell HTL trainers and Sikorsky HO-3 SAR aircraft. When the squadron transferred from Lakehurst to Miramar, skipper Maurice Peters and six other plank owners became the first helicopter pilots in the nation to make transcontinental helicopter flights since CAPT Clayton Marcy in 1945. Among them was Major Armond Delalio, USMC (not pictured) who proved so instrumental to the development of Marine Corps rotary wing aviation, that the elementary school at MCAS New River, NC was named to honor him. The squadron was redesignated as HC-1 on 1 July 1965. By 1966, HC-1 was large enough to form four other squadrons: the Seawolves of HA(L)-3, The Pack Rats of HC-3, The Providers of HC-5, and the Sea Devils of HC-7. Of these, only HC-3 remains, although now known as the Merlins of HSC-3. HA(L)-3 disestablished in 1972. HC-5 became HSL-31 on 1 March, 1972, which disestablished in 1992. A new HC-5 (currently the Providers of HSC-25) was established in 1984. HC-7 disestablished in 1975. HC-1 itself was disestablished in 1994.

HU-1 commissioning 1948 1b

15 May 1948. Commissioned at NAS Lakehurst, NJ on 1 April, 1948, the Navy’s first West Coast helicopter squadron opened for business at their new home at NAAF Miramar, CA. The original “Fleet Angels” of Helicopter Utility Squadron One (HU-1) consisted of 16 officers, 80 enlisted men, and a handful of Bell HTL trainers and Sikorsky HO-3 SAR aircraft. When the squadron transferred from Lakehurst to Miramar, skipper Maurice Peters and six other plank owners became the first helicopter pilots in the nation to make transcontinental helicopter flights since CAPT Clayton Marcy in 1945. Among them was Major Armond Delalio, USMC (not pictured) who proved so instrumental to the development of Marine Corps rotary wing aviation, that the elementary school at MCAS New River, NC was named to honor him. The squadron was redesignated as HC-1 on 1 July 1965. By 1966, HC-1 was large enough to form four other squadrons: the Seawolves of HA(L)-3, The Pack Rats of HC-3, The Providers of HC-5, and the Sea Devils of HC-7. Of these, only HC-3 remains, although now known as the Merlins of HSC-3. HA(L)-3 disestablished in 1972. HC-5 became HSL-31 on 1 March, 1972, which disestablished in 1992. A new HC-5 (currently the Providers of HSC-25) was established in 1984. HC-7 disestablished in 1975. HC-1 itself was disestablished in 1994.

HU-1 commissioning 1948 1c

15 May 1948. Commissioned at NAS Lakehurst, NJ on 1 April, 1948, the Navy’s first West Coast helicopter squadron opened for business at their new home at NAAF Miramar, CA. The original “Fleet Angels” of Helicopter Utility Squadron One (HU-1) consisted of 16 officers, 80 enlisted men, and a handful of Bell HTL trainers and Sikorsky HO-3 SAR aircraft. When the squadron transferred from Lakehurst to Miramar, skipper Maurice Peters and six other plank owners became the first helicopter pilots in the nation to make transcontinental helicopter flights since CAPT Clayton Marcy in 1945. Among them was Major Armond Delalio, USMC (not pictured) who proved so instrumental to the development of Marine Corps rotary wing aviation, that the elementary school at MCAS New River, NC was named to honor him. The squadron was redesignated as HC-1 on 1 July 1965. By 1966, HC-1 was large enough to form four other squadrons: the Seawolves of HA(L)-3, The Pack Rats of HC-3, The Providers of HC-5, and the Sea Devils of HC-7. Of these, only HC-3 remains, although now known as the Merlins of HSC-3. HA(L)-3 disestablished in 1972. HC-5 became HSL-31 on 1 March, 1972, which disestablished in 1992. A new HC-5 (currently the Providers of HSC-25) was established in 1984. HC-7 disestablished in 1975. HC-1 itself was disestablished in 1994.

HU-4 Bell HUL-1 Helicoper 1960-65

A Bell HUL-1 of the Invaders of HU-4 on deck of an unknown ship sometime between 1960 and 1965. I have been advised that the ship is possibly USS Northampton (CC 1) after conversion to a command and control ship. HU-4 became HC-4 in 1965 and HSL-30 in 1972. For those of you who may be curious, there never was an HT-35. “HT” was the squadron tail code that stuck with them all the way through their HSL days.

HU-2 HUP-2 Landing USS Midway CV-41

HUP-2 Retriever of HU-1, possibly inbound to USS MIdway (CV 41) sometime in 1963.