HC-7 RESCUE 118(1) 6-Sep-1972 (Thursday)

HH-3A Sikorsky Seaking helo Det 110 Big Mother #71

USS Gridley (DLG-21) Combat Day (2)

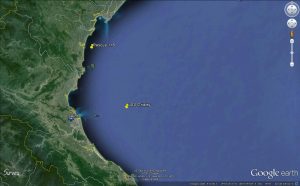

5 miles off North Vietnam coast

Water: 80⁰ Air: 85⁰ Wind: 15 knots Sea State: 10-12 feet

Pilot – LCDR Frank C. Koch

Co-pilot – LT Gene E. Gilbert

1st crew – ADJ-2 Timothy M. McCarthy (swimmer)

2nd crew – AE-3 Gary M. Tremel

3rd crew – ADJ-2 Miguel W. Melendez

Alert received – 1745: via radio

Vehicle departed – 1751: 50 miles –

Arrived on scene – 1815 :

Located survivor – 1816: radio vectors – heavy seas, dusk

Begin retrieval – 1819: Helo hoist

Ended retrieval – 1820: hoist

Survivor disembarked – 1900: aboard ship – USS Gridley

A-4F Skyhawk NP-304 (Flying Eagle 304) 155021 VA-212, USN,

USS Hancock (CVA-19)

Lt Willard F. Pear

Later in the day a pair of Skyhawks on an armed reconnaissance mission found several trucks on a coastal road about 10 miles south of Thanh Hoa. As Lt Pear was about to pull up from his second pass at 5,000 feet his aircraft was hit in the tail by 23mm flak. He turned towards the sea with the aircraft on fire and the engine winding down slowly. About five miles out to sea the controls suddenly froze and the aircraft started to roll to the left so Lt Pear ejected. He was later rescued by a Navy helicopter. This was the last of 12 aircraft lost by the Hancock before completing its seventh tour on 25 September. The ship would return to Vietnam on 19 May 1973 for her eighth war cruise, a record for any TF 77 carrier, but no further aircraft were lost on her final tour. The USS Hancock was decommissioned on 30 January 1976 and was subsequently scrapped. (5)

(19:02) (12) Recover Big Mother 71, downed pilot Lt W.F. Pear – from VA-212, USS Hancock

Total SAR time – this vehicle – One hour and 30 minutes.

STATEMENT OF PILOT – LCDR FRANK C. KOCH, USN

At approximately 17:45 (Sept. 6, 1972), the pilot was in CIC when notification of the ejection was received on the attack frequency. The helo detail was set immediately and the helicopter was airborne in six minutes. En route to the scene the crew prepared for an opposed water pick-up. Radio reception was excellent with the controlling ship until nearing Hon Me Island at which time the helicopter descended to 50 feet MSL and secured IFF and external lights in an attempt to avoid detection. At this time contact was established with the On Scene Commander and Rescap on button five UHF, they then provided vectors. Button two UHF was being monitored by the co-pilot as the survivor was up on that frequency. Initially we were vectored too close to the beach and the survivor turned us back to seaward toward him. Then it was a combination of vectors from Rescap and the survivor that enabled us to find him.

(The helicopter was masked from the survivor by high waves and the helicopter’s low altitude.)

A swimmer was dropped to aid the survivor and the helicopter departed the hover to starboard in a diversionary tactic. A smoke flare was dropped about ½ mile southeast of the two men in the water. Rescap then announced that they were ready to be picked up. (At this time the aircraft commander realized that in attempting to provide a diversion, he had neglected to maintain a visual position on the survivor.) Rescap was requested to provide vectors back to the survivors and they were sighted shortly thereafter. With the rescue helicopter in a hover, the sling was lowered. The swimmer had difficulty in hooking the survivor to the cable. (Explained in the swimmer’s statement.) During this phase firing could be heard from the beach and the co-pilot observed splashes in the vicinity of the smoke flare. At this time Rescap began bombing the CD and AAA gun sites in an attempt to silence them. (The bombing continued until the helicopter was well clear) As soon as the two men were, clear of the water the helicopter departed its hover and exited the hostile area. It was determined that the survivor was not seriously injured and the helicopter returned to the DLG. (By having the co-pilot communicate with the survivor on one UHF and with the pilot talking to Rescap and the OSC on the other UHF radio transmissions were kept to a minimum and likewise confusion. The survivor’s vectors were the ones that counted in the final stages. Without them, he would have been very difficult to find in the heavy seas, again illustrating that the survivor is his own best rescue aid.)

STATEMENT OF PILOT – LT GENE E. GILBERT, USN

We were on deck USS GRIDLEY, (Sept. 6, 1972), when SAR alert was passed. We immediately manned the aircraft and launched (approximately 6 minutes). Once airborne we received a vector from the ship and headed for the downed pilot, we were informed that he was 45 to 50 miles north and one to two miles off of the coast. We established contact with Rescap and learned that the downed pilot appeared to be in good condition. We informed Rescap that we would arrive on the scene in 20 minutes and we did not want the survivor to use a signal smoke due to his proximity to the coast and due to the fact that enemy fire had been noted in area.

Our vector was taking us close to Hon Me Island so we requested an escort from Rescap to suppress any fire we might encounter. When Rescap informed us that we were in the SAR area I switched to SAR Secondary frequency and established contact with the downed pilot and asked him to vector us to his position. The survivor gave us very clear precise vectors and we soon saw him directly ahead at about 200 yards.

We transitioned to a slow speed over the downed pilot and dropped an air-crewman into the water to prepare the survivor for pick-up. We then move approximately 300 yards south of he survivor and dropped a signal smoke in the water as a diversionary tactic. We lose sight of the survivor momentarily as we turned back toward him for the pick-up but soon regained visual contact. As we transitioned into a hover over the downed pilot I noted smoke from the beach and observed a splash in the water approximately 500 yards in toward the beach and to the south of the pick-up point. 23mm anti aircraft fire was also noted. At this time Rescap began strafing and bombing the beach to suppress enemy fire. We hovered over the survivor for approximately 2 minutes and as soon as the air-crewman and survivor were clear of the water, we transitioned to forward flight and began to depart the area. We then proceeded to the ship with the survivor.

REPORT OF THE RESCUE OF “WILLARD PEAR”

BY: ADJ2(AC) T. McCARTHY

It was late afternoon on the 6th of September, (1972), we were on the helo deck of the USS GRIDLEY, we had just secured the bird for the night. Flight quarters was announced but we didn’t move, we thought we’d wait for LCDR KOCH to tell us what was up. He came running out and said “We got one!, we got one!” Myself and the other two crewman broke down the high point tie downs and pulled the intakes (covers) and blade boots. By this time #1 engine was going and within minutes we were off the deck. We got vectors to the scene. The reason for our having three crewman was the fact that MELENDEZ and TREMEL were on a check-ride for first crew. The check-ride had been completed to my satisfaction so I decided that now the best test could be given, I’d enter the water as the swimmer. Both TREMEL and MELENDEZ prepared for the rescue. We were now one mile off the beach and we were looking for our man. He saw us and vectored us to him. Now he was on our nose and we went in for the drop. The drop was good and I told the man to roll out of his raft. I check him over for injuries and to ensure that he wasn’t tangled in his anchor or any shroud lines. He was clear. I told him to call the bird on his radio and tell them we were ready. I turned around to sink his raft. Now was the first time it occurred to me that we were taking fire, I could hear it but I couldn’t see any splashes. After slashing his raft I turned around to find us 15 feet apart and now was the first time it occurred to me that the waves were 10-12 feet high. I swam back to him and told him to splash, that was the signal. He splashed like crazy. When the bird was on final, I asked him for his “D” ring. He was excited and was looking on the wrong side. I found his snap link and hooked it into mine. He had a funny hook up with two hooks and his snap link through a web strap. The hook came to me and I snapped my snap link to the hook but the bail wouldn’t close, I tried it again not wanting to go up like that for fear of falling out. Finally, I undid half of the rescue collar and then the bail closed. I gave the crewman a thumbs up and away we went. As we were clear of the water, the helo started forward. We started to swing a lot but the crewman did a good job of stopping our movement before we got to the underside of the bird.

Now as I think back I can’t figure out why the bail wouldn’t close, might have been his harness but I’m not sure.

STATEMENT OF RESCUE

BY: ADJ2 (AC) MIGUEL W. MELENDEZ

At about 1700 Big Mother, (Sept. 6, 1972), had just been secured for the night. The crew, excepting our pilot, LCDR KOCH, who was in CIC, were sitting around the aircraft, thinking this was going to be an uneventful evening. One minute later we heard over the 1 MC that flight quarters was being set. At that time, we didn’t know exactly why. We thought that maybe a log helo was about to come in or something of that sort. An instant later we saw Mr. KOCH running to the helo and yelling, “We got a man down in the water”. Everyone started scrambling to get the aircraft broken down and ready for an expeditious take-off. We had a few minor problems consisting of slight delay in hooking up electrical power and part of the tie-down chain on the left main mount. AE3 TREMEL jumped out of the helo to clear the left main mount. Lift-off took about six minutes. Monitoring the radios, Rescap gave us a sit rep and vectors to the downed pilot. It took us approximately thirty minutes to reach the survivor. At one time during the flight, we were within one mile of the beach. We were all aware of possible opposition in our rescue attempt. Rescap assured us we had plenty of protection. All during the flight ADJ2 McCATHY, who was giving AE2 (3) TREMEL and me a first crew check-ride, was in his swim gear as we made previous plans during the day, that McCARTHY would be the swimmer. On our final vector, we had the survivor insight. McCARTHY jumped out and landed within 2 to 3 feet of him. The pilot flew the aircraft a few hundred feet to drop a dummy smoke to cause a little confusion. We then came back around in figure 8 pattern to pick-up the two men in the water. After the pick-up, we were directed to go back to the DLG for the night. At which time we settled down for one of these uneventful evenings.

STATEMENT OF RESCUE

BY: AE3 (AC) GARY M. TREMEL

We were on deck of the USS GRIDLEY, September. 6, (1972), approximately 5 PM. We had just been secured for the evening. It was moderately high seas, so we had 9-point tie downs and four high point tie downs. LT GILBERT, ADJ2 McCARTHY, ADJ2 MELENDEZ and myself were relaxing on the flight deck when we heard over the ships 1MC, “Man your flight quarter stations.” We were somewhat confused. For a moment, we sat and wondered if they expected to take a log helo on the bow or something of that nature. At that time LCDR KOCH came running and informed us we has a pilot in the water. As our pilots were getting in their flight gear, we started taking off the excess chains and high points etc. and started getting into flight gear ourselves. At the time, MELENDEZ and myself were getting our NATOPS check-ride, form McCARTHY. We had decided earlier that McCARTHY would be the swimmer. He was confident that MELENDEZ and I could handle things in the aircraft and wanted a chance to make a rescue as a swimmer. The flight deck crew was arriving on deck at this time and apparently did not know this was an actual SAR effort. We waited several seconds for him to hook up power, then as they stripped off chains and chocks, I noticed from my forward position that half the chain was left hanging on the port main mount. I jumped out and removed it, then we lifted off. Even with these minor mishaps it was an extremely efficient launch taking somewhere in the vicinity of 6 minutes from the time they announced flight quarters until lift off. Once airborne we got the brief and proceeded by vectors to the scene. We were in direct contact with RESCAP the whole time. Rescap was standing by with ordnance as we passed approximately one mile off Hon Me Island. At that time, RESCAP began directing us to the downed pilot. We were moving north along the coast and were instructed to continue for about 12 more miles. McCARTHY had been in swim gear and standing by for some time now and MELENDEZ was busy rigging the hoist and making sure we had the proper pyrotechnics at hand. I was stationed at the forward M-60 mount and instructed to look for fire from the beach. We heard Rescap calling out gun positions on the breach but I was only moderately concerned as I heard Rescap also say they had plenty of protection for us. As we started to get close to the survivor McCARTHY was positioned in the cargo door. We had realized there was a very high sea state in the area and planned to drop the swimmer as close as possible to the survivor. We made a very good approach and dropped McCARTHY within 3 feet of eh survivor. We then started to move forward and also got “thumbs up” for the swimmer. After proceeding several hundred yards, we dropped a MK-25 smoke and proceeded in a figure 8 pattern. During this time due to the high sea state, we lost sight of the survivor. Rescap began vectoring us on for the pick-up and we got word from McCARTHY and the survivor that they were ready to be pick-up. MELENDEZ got sight of the survivor and began talking the pilot in. I was operating the hoist and began letting out cable when I saw them just in front of us. MELENDEZ was directing the helo into a hover over the survivor an I was trying to get the horse collar to them the best I could. The swells kept moving McCARTHY and the survivor out of position and it was rather difficult to get the hook to them. Once McCARTHY had the hook he had some difficulty attaching to it due to darkness of the water (limiting his underwater visibility) and position of the pilots snap link. During the hook-up, which seemed to take a long time, I could hear distinct explosions above the sound of the aircraft. I wasn’t sure if it was fire from the beach or bombs being dropped by our attack aircraft. Once the survivors were attached to the cable, I started the hoist up. We started moving forward slowly causing the cable to swing, but MELENDEZ and I stabilized it before it reached the sponson. After we had both survivors in the aircraft, MELENDEZ told the pilot to “BOOK” and at that time, we proceeded back to land on the deck of the USS GRIDLEY. I felt it was an efficient rescue all the way around. The flight deck situation may have been improved if there had been something said about an actual SAR condition, and flight deck crews putting more emphasis on planned efficiency and co-ordination rather than acting hastily. I felt that Rescap did an outstanding job and the whole SAR effort was done in a professional manner.

From: Frank Koch Sent: Friday, January 11, 2008 Subject: Will Pear Rescue

I think I’m the pilot that made that rescue. We did take fire from the beach and had to jink to throw them off. We dropped a decoy smoke for them to shoot at. Unfortunately, we neglected to keep the rescue swimmer and survivor in sight while jinking and dropping the decoy smoke and it wasn’t a “glassy sea” which made for some interesting conversation while we tried to relocate the swimmer and survivor. I had a picture of the skipper of the Oriskany (I think that was the carrier), Will, and I with a cake celebrating his rescue. Unfortunately, most of my memorabilia was lost when Katrina flooded our home in Pass Christian, MS. • My co-pilot was Gene Gilbert. When I ordered the rescue Swimmer to “Jump, jump, jump.” He thought I said “Dump, dump, dump.” and started dumping fuel. That didn’t go well with the swimmer and survivor, who got face full of JP-5. • Unfortunately, I don’t recall the names of the swimmer and the rescue air crewman, I think I could pick them out of a list. (Phil, can you help me out here.) Maybe the swimmer was Tim McCarthy… • I do remember that I had permission from CTF-77 to carry splits of Paul Masson Very Cold Duck in the helos to celebrate when we made a rescue. Usually the survivor would be too stressed out to drink very much and the rescue air crewmen had to finish it off. • I received a DFC for the rescue. I think the swimmer received a Navy Comm and the co-pilot and rescue air crewman each received single action Air Medals.

1) Numbering as per HC-7 Rescue Log (accumulative rescue number)

2) HC-7 Rescue Log

3) HC-7 Det 110 Rescue report

4) Map – Goggle Earth

5) “Vietnam – Air Losses” By: Chris Hobson (with permission)

6) Loss aircraft location data provided by: W. Howard Plunkett (LtCol USAF, retired)

10) HC-7 History collection; Ron Milam – Historian

12) USS Gridley – Deck Logs

Further Reference:

“FOUNDATION” Vol-29, Number 2, Fall 2008 – by: Commander Charles “Chuck” Sweeney, USN (Ret.)

“SUMMER of ‘72”

(Compiled / written by: Ron Milam, HC-7 Historian – HC-7, 2-1969 to 7-1970, Det 108 & 113)